The ever‑growing UAFX stompbox line‑up now includes a range of more affordable single‑function digital pedals: 1176 Studio Compressor, Orion Tape Echo, Heavenly Plate Reverb and Evermore Studio Reverb.

There’s perhaps no better example of the old adage that you can’t please all of the people all of the time than Universal Audio’s foray into the effects pedal market. In 2019 their Starlight Echo and Golden Reverberator pedals were received with a mixture of wonder at how beautiful they sounded and frustration at the absence of MIDI control and limited preset handling. The amp‑sim pedals that followed polarised the user‑base still further: guitar players now seem to have an expectation of access to presets and MIDI control, as it is rare to find an amp modeller without plenty of both. There was widespread, forum‑led expectation that ‘the next thing’ would fix all that, but ‘the next thing’ was Del‑Verb, Galaxy and Max: still no MIDI, and the control app now really just provided options and pre‑configuration, rather than actual presets. They were again great‑sounding digital pedals, but with a user interface so WYSIWYG that they almost could have been analogue.

Overview

UA’s latest releases in their pedal line‑up are immediately differentiated by a smaller enclosure than the earlier models, and a single footswitch, the latter also only functioning as an effect on/off switch: there are no preset recall, tap‑tempo, or user‑definable functions. Similarly, the rest of the controls have a single function, working in conjunction with a couple of set‑and‑forget switches just above the top‑mounted jacks providing input and output. One input and one output on TS jacks tells you that these are mono pedals and that will, no doubt, be a source of disappointment for some, given that two of these pedals are reverbs and one is a delay.

The full line‑up in this batch consists of: the Orion Tape Echo, which emulates a vintage Maestro Echoplex EP‑III tape delay; the 1176 Studio Compressor emulation of the company’s popular FET compressor; the Heavenly Plate Reverb, which is based on various versions of the EMT Plate 140; and the Evermore Studio Reverb, a bit‑for‑bit rendering of a Lexicon 224 (some of the specific product emulation attributions here are mine, not UA’s).

So, who are these for? “The definitive UA 1176 compressor, now on your pedalboard,” say UA, suggesting that guitarists’ pedalboards, where mono is far more common than stereo, is obviously one intended usage. But, given the lower price than the previous pedals and the fact that they can all take a decent amount of line level, up to +12dBu, I think the potential user‑base is wider than just performance use for guitar players.

1176 Studio Compressor

UA’s classic 1176 FET compressor was one of the emulations included in their recent Max preamp/compressor pedal, but this incarnation has two additional modes, Dual and Sustain, in which two 1176 models are cascaded to achieve some very specific effects that I’ll come to later. Controls consist of input level, output, attack, release and ratio, plus a three‑position mode selector. There are also switches for true or buffered bypass and parallel‑compressor operation, placed next to the audio jacks and the DC power input (9V, minimum 250mA capacity, with no battery option). There’s no Bluetooth for internal software settings, and the USB‑C port, as in the previous pedals, is used solely for firmware updates.

The 1176 Studio Compressor.In Single mode, the pedal behaves very much like an 1176. If you’re unfamiliar with compressor types and their characteristics, it’s important to understand what you’re getting here. Guitar players using compression on a pedalboard often want to hear it clearly changing the envelope of the sound — they want it as an effect. The 1176 doesn’t really do that. Even with the attack and release at their slowest, it is still fast, and will generally be trying to give you controlled dynamics without obvious side‑effects. It’s the polar opposite of the ‘pop and surge’ sound of a DynaComp, and whilst you can use it for a more consistent drive into an amp or pedal, it perhaps does its best work best at the end of a pedal chain, on its lowest ratio, just controlling overall dynamics by reducing the level difference between driven and clean tones.

The 1176 Studio Compressor.In Single mode, the pedal behaves very much like an 1176. If you’re unfamiliar with compressor types and their characteristics, it’s important to understand what you’re getting here. Guitar players using compression on a pedalboard often want to hear it clearly changing the envelope of the sound — they want it as an effect. The 1176 doesn’t really do that. Even with the attack and release at their slowest, it is still fast, and will generally be trying to give you controlled dynamics without obvious side‑effects. It’s the polar opposite of the ‘pop and surge’ sound of a DynaComp, and whilst you can use it for a more consistent drive into an amp or pedal, it perhaps does its best work best at the end of a pedal chain, on its lowest ratio, just controlling overall dynamics by reducing the level difference between driven and clean tones.

Though in pedal format, this is perfectly usable on a line‑level insert as a recording hardware compressor for any of the sources 1176s are often used with, such as vocals or bass: it’s comfortably quiet enough in terms of self‑noise. The 1176 has no actual threshold control: the threshold is nominally ‘fixed’, so the input gain determines how far above it you want the signal to go. In practice, though, the threshold value increases a little when you select higher ratios, so if you just increase the ratio you’ll see less gain reduction until you raise the input signal a little.

There’s a switchable Parallel mode, but it’s a bit of a fudge. This is a digital pedal, so there’s a tiny amount of latency (about 2ms), which means just putting it on an aux send to create a parallel path would result in some comb‑filtering cancellation. The ‘fix’ is a dry, parallel path within the pedal, delayed by the same amount, so that it will combine non‑destructively, but the dry path has a set level (50:50 mix with the processed signal), and given that the input gain is used to set the amount of compression and both dry and compressed signals are subject to the output level, there’s no way of achieving your own dry/comp mix.

As on the original hardware 1176, the attack and release controls give you faster operation as you turn the controls up (clockwise) as opposed to setting a longer attack or release time by turning them up. It’s counter‑intuitive if you’re not used to it, and I can’t help feeling that something on the pedal should give an indication of how these controls function: there are no marked values at all.

The ratio knob is a detented control with expected 1176 settings of 4:1, 8:1, 12:1, 20:1 and All, the last representing the explosive and dirty‑sounding ‘all‑ratios‑at‑once’ mode. There’s also an Off position, in which the gain reduction element is bypassed but the signal still passes through the other emulated parts of the circuit. Recording through a hardware 1176 with no compression active adds enough character to be a worthwhile option and that is also the case with the pedal. I’m not entirely sure what it is doing, but it is really rather nice! When the pedal is active, the on/off LED doubles as a simple gain‑reduction meter, with green indicating no compression, amber showing the onset of gain reduction, turning to red to indicate more compression. Not great, but certainly better than nothing.

What’s better than an 1176? Two 1176s, of course! Sustain mode offers the sound of two 1176s in series, and this is the key to the classic Lowell George (guitar player with the ’70s band Little Feat) unfeasibly long‑sustain, clean slide‑guitar sound. We’ve only got one set of controls on the pedal, and using two 1176s for this trick requires rather different settings on each unit, but that’s all taken care of ‘under the hood’ — you just tweak the controls as if it were the second unit in the chain. It certainly works: just add talent! You don’t have to use it just for slide, of course. It will do ‘long‑sustain clean’ in a very different way to, say, a DynaComp, that’s just lovely with a big wash of modulated reverb.

There’s another version of series‑connected 1176s on offer in the form of Dual mode, with one unit driving the other into distortion — a DI’ed guitar sound famously used by Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin on the track ‘Black Dog’.

There’s another version of series‑connected 1176s on offer in the form of Dual mode, with one unit driving the other into distortion — a DI’ed guitar sound famously used by Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin on the track ‘Black Dog’. Distorting direct‑injected guitars by overdriving console inputs or outboard gear was ‘a thing’ for a while in the late ’60s and into the ’70s and can be heard on a surprisingly large number of popular records of the period. The fact that the processed sound would always be recorded to analogue tape back then, however, was a significant mitigation of the absence of any sort of speaker sim. I can’t say that I was much of a fan of that sound back then, but if you think you might have a use for it, this is a really quick and easy way to get there.

Orion Tape Echo

The Orion tape echo pedal.UA’s Orion offers the algorithms from their Starlight Echo Station in a compact, simpler format, emulating the sound of a vintage ’70s Maestro Echoplex EP‑III tape delay. Like the original hardware, it is mono and has no tap‑tempo facility. The latter will, of course, rule out the Orion from consideration by a number of potential purchasers who regard ‘in‑time’ delays as an essential part of modern music making, but others who, like myself, grew up with real tape delays, may regard that as an irrelevance. Real tape delays have a very specific infidelity that lends itself perfectly to the combination of an electric guitar and a tube amplifier. There’s something magical arising out of that whole signal chain that simply doesn’t exist in any other combination of elements, and whilst I can’t claim to have heard every tape‑emulation pedal, I can say that I have yet to hear it done better than in these UA modelled versions.

The Orion tape echo pedal.UA’s Orion offers the algorithms from their Starlight Echo Station in a compact, simpler format, emulating the sound of a vintage ’70s Maestro Echoplex EP‑III tape delay. Like the original hardware, it is mono and has no tap‑tempo facility. The latter will, of course, rule out the Orion from consideration by a number of potential purchasers who regard ‘in‑time’ delays as an essential part of modern music making, but others who, like myself, grew up with real tape delays, may regard that as an irrelevance. Real tape delays have a very specific infidelity that lends itself perfectly to the combination of an electric guitar and a tube amplifier. There’s something magical arising out of that whole signal chain that simply doesn’t exist in any other combination of elements, and whilst I can’t claim to have heard every tape‑emulation pedal, I can say that I have yet to hear it done better than in these UA modelled versions.

When tape delays first appeared there were no guitar amps with effects loops, so the delay went straight into the front of the amp, giving a rather different sound and dynamic effect from a post‑preamp distortion delay in a loop. With many modern amp designs built around a lot more preamp distortion, delay into the front end doesn’t always work, but the Orion, as with all the UAFX, has enough headroom to operate well with any amp send‑return loop.

Whilst I can’t claim to have heard each and every tape‑emulation pedal, I can say that I have yet to hear it done better than in these UA modelled versions.

The five‑control layout is simple and intuitive. Delay time ranges from 80 to 700 ms, just like the original hardware; 80ms isn’t short enough for classic ‘slap’, but the softer tonality of ‘tape’ somehow makes it still work. In the ‘practical zone’ for an always‑on delay, say 350 to 450 ms with a low mix and a single repeat, the same tonal qualities just keep the delays in their place, supporting without shouting ‘listen to me’. The tonal character can be tweaked from Mint (a brand‑new machine with new tape and integral noise reduction), through Worn (slightly used tape on a decently‑maintained early‑’70s machine with no noise reduction) to Old (a less well‑maintained unit, with very worn tape resulting in wow & flutter in the echoes). You can also dial in some modulation in the other settings, using the Wonk control — a little is usually enough! Just like a real tape delay, you’ll hear the pitch change if you adjust the Delay control while there is audio sounding.

There’s also another ‘character’ variable in the Record level control, as this sets how hard the tape is driven, achieving first saturation compression and then distortion as it is increased. Feedback sets the number of delay repeats, with runaway oscillation available at high feedback settings, and Mix sets the balance of delay and dry signals, with 100 percent wet available when the mix control is fully clockwise.

The preamp in a real EP‑III is always active on both delayed and dry signals, either ‘fattening the tone’ or ‘losing some high end’, perhaps depending on how much you already like the sound of your amp. But here you get a choice using the little slide switch on the back to remove the modelled preamp from the dry path (it’s always active on the delay path), offering an all‑analogue dry through path. If you are one of those people who like the sound of it, you’ll probably want its influence to remain even if you turn the delay off via the footswitch, but fortunately all possible options are catered for by the combinations of the Bypass and Preamp switches, including true or buffered bypass and trails or not when switching.

Heavenly Plate Reverb

This one offers a mono, compact‑pedal version of the luscious EMT Plate 140 emulation used in UA’s Golden Reverberator pedal and plug‑in. A mono reverb on a pedalboard is perfectly fine, I think, unless you are running a full stereo or ‘wet‑dry‑wet’ rig, in which case you’ll probably be choosing a processor with more options anyway. If you are seeing one of these as both a guitar pedal and an affordable route into a very nice hardware reverb for recording and mixing, you might see the lack of stereo as a limitation. Personally, I often prefer a mono reverb in a recording/monitoring context, and this one in particular has a spaciousness that just works. Real plate reverbs aren’t really very ‘stereo’ at all anyway, just relying on the slightly different tonality of two pickups at opposite ends of the metal plate.

The Heavenly Plate Reverb.The controls are delightfully simple. Decay sets the reverb tail length, from 500ms up to a maximum of five seconds. Mix is self‑explanatory, but does offer 100 percent wet when fully clockwise, facilitating use on a send. There are three ‘plate types’ to choose from: A emulates an “older plate with a brighter, more rolled‑off response and a shorter decay”; B is an “older plate with a darker, more muted tone, and a slightly longer decay”; while C gives you the sound of “a newer plate with a more even overall frequency response, longer decay, and some natural warble as it decays”. Pre‑delay shifts the onset of the reverb signal away from the dry sound, with a range of zero to 250ms, and makes for a much clearer overall sound, especially in mono.

The Heavenly Plate Reverb.The controls are delightfully simple. Decay sets the reverb tail length, from 500ms up to a maximum of five seconds. Mix is self‑explanatory, but does offer 100 percent wet when fully clockwise, facilitating use on a send. There are three ‘plate types’ to choose from: A emulates an “older plate with a brighter, more rolled‑off response and a shorter decay”; B is an “older plate with a darker, more muted tone, and a slightly longer decay”; while C gives you the sound of “a newer plate with a more even overall frequency response, longer decay, and some natural warble as it decays”. Pre‑delay shifts the onset of the reverb signal away from the dry sound, with a range of zero to 250ms, and makes for a much clearer overall sound, especially in mono.

Reverb‑tail tonality can be tweaked: left of centre cuts highs and adds low end. Turning to the right does the opposite, and you can also add some gentle modulation to the tail, chorus‑like on the Slow setting and more prominent but less useful on the Fast, in my view. True hardware bypass is available from the footswitch, at the expense of cutting off any tail sounding at the time, or you can opt for a buffered mode in which decays will still fully decay even after you have bypassed the pedal. If you are using this on a guitar pedalboard it is probably going to be right at the end of the chain where a buffer is never a bad thing.

A real plate reverb in the studio would generally only have been applied to sources as a live‑monitored signal, and not recorded until it was integrated as part of the final mixdown. Plates were designed to give a dense, smooth ambience to a wide variety of signals, from vocals to snare drum and everything in between. When we hear plates on guitars in recordings they are usually applied to a miked‑up speaker signal. Whether or not those same sound qualities lend themselves well to going in the front end of a guitar amp and being heard via the limited response of a guitar speaker is arguable, and perhaps dependent on how clean or dirty you run your amp. Of course, many people use modellers instead of real amps these days, and that makes it easy to place a reverb pedal post‑amp and speaker sim, but many of those processors will contain stereo effects that will have to be collapsed to mono in order to use one of this generation of UA effects, unless you are using a mixer and can put it on a send with a 100 percent wet mix. Monitoring a dry guitar and a mono reverb panned just slightly apart is actually a really nice ‘comfort effect’ for recording, I find. Heavenly, you might say.

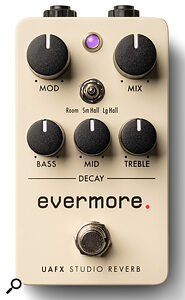

Evermore Studio Reverb

I started out as an engineer in pro studios just in time for the arrival of the Lexicon 224 digital reverb. I happily sat for hours listening to all the sounds you could make by tweaking the parameters, mostly marvelling at how ‘real’ it sounded compared to the plate reverbs we were all using. Of course, compared to later generations of digital reverbs, the 12‑bit architecture of a 224 doesn’t sound real at all, but I haven’t lost that sense of what ‘reverb as an effect’ should sound like. Of course, it was horribly overused on records throughout the ‘80s, but I believe it still has its place in the effect vocabulary. There’s no getting away from it, I do miss stereo on this one, because the Evermore sounds exactly like a 224, just without the wide spaciousness of the stereo versions in UA’s Golden Reverberator and Del‑Verb.

The Evermore Studio Reverb.There are three basic algorithms: Room, with high initial density and low coloration; Small Hall, with moderate initial density and non‑uniform decay; and Large Hall, optimised for long reverb times with low density and little coloration. These work in conjunction with the three Decay controls, Mid, Bass, and Treble. These aren’t filters or EQ controls but directly set the reverb decay time for the frequency bands they address. For the most predictable results, set the desired reverb decay time with the Mid knob, then tweak Bass and Treble decay to achieve the overall effect you want. It’s actually an incredibly fast and intuitive way to dial up specific reverb tones, especially on the shorter settings where you can treat it like a mono virtual ‘room mic’ and quickly decide how much weight or presence you want from the room. Just as with the vintage hardware, you can quickly get yourself into major artefact territory by getting the bands a long way from each other, but there’s a lot of sonic fun to be had along the way!

The Evermore Studio Reverb.There are three basic algorithms: Room, with high initial density and low coloration; Small Hall, with moderate initial density and non‑uniform decay; and Large Hall, optimised for long reverb times with low density and little coloration. These work in conjunction with the three Decay controls, Mid, Bass, and Treble. These aren’t filters or EQ controls but directly set the reverb decay time for the frequency bands they address. For the most predictable results, set the desired reverb decay time with the Mid knob, then tweak Bass and Treble decay to achieve the overall effect you want. It’s actually an incredibly fast and intuitive way to dial up specific reverb tones, especially on the shorter settings where you can treat it like a mono virtual ‘room mic’ and quickly decide how much weight or presence you want from the room. Just as with the vintage hardware, you can quickly get yourself into major artefact territory by getting the bands a long way from each other, but there’s a lot of sonic fun to be had along the way!

A major part of ‘the Lexicon sound’ defined by the 224 is the inherent amount of modulation in the reverb decay, controllable here with the Mod knob with a range from barely perceptible, through subtle chorusing to way too much. A bit more control resolution in ‘the sensible zone’ would have been nice for this one though. The rotary control line‑up is completed by the mix knob, with 100 percent wet available for use on an aux send. A fixed amount of pre‑delay is available via one of the mini slide switches, along with true or buffered bypass, with the dry signal remaining in the analogue domain.

Personally, I’m not sure I’d choose to have a Lexicon 224 sound as a reverb on a guitar pedalboard, but its distinctive sound is always lovely to have available as a flavour for recording, used as a post‑amp effect.

The Orion delay and Heavenly reverb are absolute gems and I don’t care at all that they are mono.

Summing Up

Of the three groups of UAFX products I’ve had for review, this set is the one I was most sceptical about, but I have to say they have won me over. The Orion delay and Heavenly reverb are absolute gems and I don’t care at all that they are mono. They work equally well in front of an amp or as a post‑miking effect. I miss the stereo aspect of a real 224 in the Evermore, but the immediacy of the three band‑decay controls offers a degree of creative tweakery beyond anything in UA’s other Lex emulations by way of compensation. The 1176 does what an 1176 does and as such, I see it less as a guitar pedalboard effect and more as a DI recording tool, or indeed as an affordable hardware 1176 option if you pair it with a mic amp or use it on an insert point.

These pedals are more affordable and more focused than their predecessors, with no dual modes, no presets, no Bluetooth, no app to think about. Just great-sounding effects with a simple, intuitive user interface. If not for everybody, they are most definitely for somebody.

Pros

- They sound great! All of them.

- Very easy to use.

- More affordable than the bigger pedals.

- Just the effect you want, not paired with something you don’t.

Cons

- The reverbs and delay being mono won’t please everyone.

Summary

They are smaller, simpler, more affordable and mono. For some users in some applications, exactly what you’d want whilst keeping the same great UA sound.

Information

£165 to £189 each, depending on model. Prices include VAT.

1176 Studio Compressor $199. Other pedals $219 each.